This post documents an interesting tidbit that I discovered back in June of this year while doing some reading meant for my summer work. (Specifically, my Discord logs seem to say June 10th, when I shared my findings with other UGA grad students.) I never shared this information here, mostly because I completely forgot this blog existed, but I’d like to write up because I find it interesting and I don’t think this is broadly known.

My summer reading was meant to be on Ramakrishan and Valenza’s book Fourier Analysis on Number Fields, a friendly summary of the preliminary results needed to understand Tate’s thesis. I was surprised to learn that “algebraic” number theory has a ton of analysis involved; the underlying Fourier analytic tools are so useful that they provide a very powerful reformulation of Hecke’s earlier results on Hecke L-functions. In particular, the adele ring attached to a global field contains a ton of arithmetic information; as a locally compact abelian (LCA) group, it also carries over the Fourier analytic techniques developed in harmonic analysis to get us cool results. I wish I could say more, but unfortunately I understand too little. Maybe one day I will be able to understand Matt Emerton’s Stack Exchange post on the matter…

At any rate, in an effort to understand all of this wonderful nonsense, I was reading Bjorn Poonen’s very nice notes. I only made it to the top of page 2 before something caught my eye.

Hecke in 1918–1920 generalized Theorem 1.1 to Dedekind zeta functions $\zeta_K(s)$, and then quickly realized that his method applied also to Dirichlet $L$-functions and even more general $L$-functions. Tate in his 1950 Ph.D. thesis (reprinted in [Tat67]), **building on the 1946 Ph.D. thesis of Margaret Matchett (both of them were students of [Emil Artin](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emil_Artin))**, gave an adelic variant of Hecke’s proof. (bolding mine)

I found this interesting. I’d done enough reading at this point to recognize names of mathematicians, but I hadn’t previously heard of Margaret Matchett. This struck me as even more extraordinary given (an educated guess from the name) that this was a female mathematician doing number theory in 1946?! I had to learn more. And there was something interesting about that name Matchett; it was ringing a bell…

I googled Margaret Matchett and clicked on the very first result.

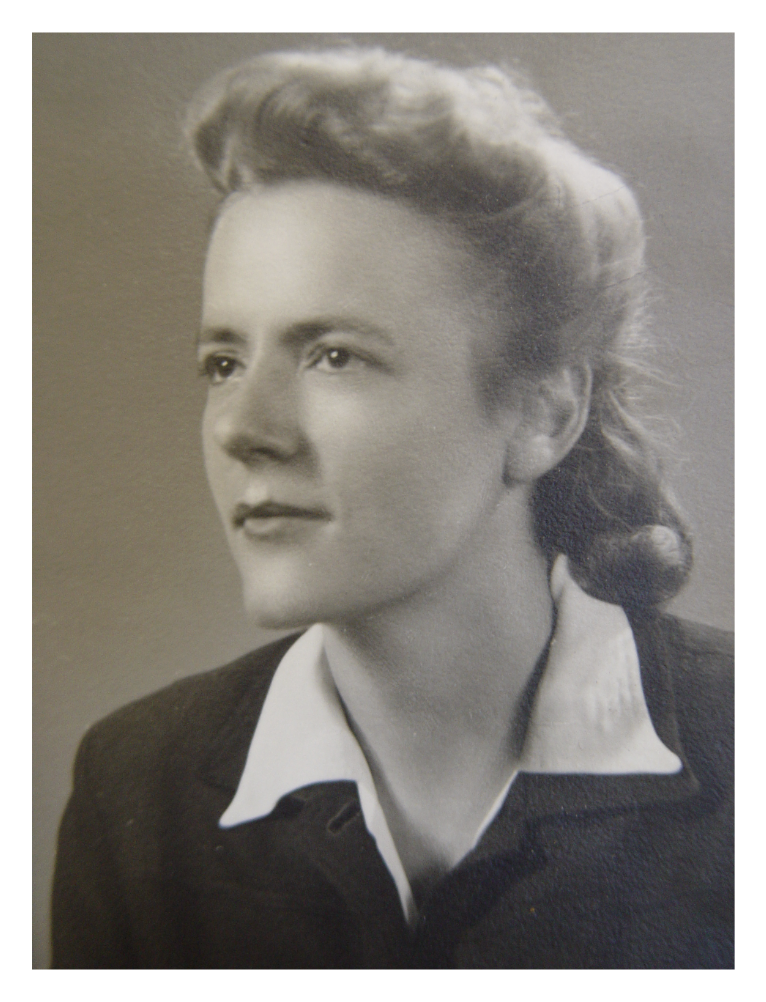

Margaret Matchett

Ph.D. Indiana University 1946

Dissertation: On the Zeta Function for Ideles

Advisor: Emil Artin

No students known.

So indeed she was a student of Artin. Interestingly enough, she had no students, which I supposed made sense. If she had students, presumably her name would’ve been “out there” more than it already was. (I also didn’t know that Artin had spent time in Bloomington, which must’ve been quite the jump from Zürich!) Even more intrigued, I decided to look farther. Perhaps it was worth investigating Tate’s words himself.

Consulting my copy of Cassels and Fröhlich (courtesy of Commonwealth Books), whose last chapter is a full copy of Tate’s thesis, Tate himself does mention Matchett in his historical introduction (and where I assume Poonen got his citation from). In a brief summary, he describes a program started by Hecke with his $\zeta$-functions, and continued by Chevalley, who introduced the idea of the idèle group in 1940. (A work, as an amused Tate remarks, whose “main purpose was to take analysis out of class field theory.”) Artin and Whaples, in 1945, then defined “valuation vectors” (now called adèles) and derived “from simple axioms all of the basic statments of algebraic number theory.”

So it makes sense that, around the same time, Artin would suggest to Matchett to try to expand Hecke’s original results using this new idèlic language! As Tate explains,

Matchett, a student of Artin’s, made a first attempt (1946) to continue this program and do analytic number theory by means of idèles and vectors. She succeeded in redefining the classical $\zeta$-functions in terms of integrals over the idèle group, and in interpreting the characters of Hecke as exactly those characters of the ideal group which can be derived from idèle characters. But in proving the functional equation she followed Hecke.

Artin suggested to me the possibility of generalizing the notion of $\zeta$-function, and simplifying the proof of the analytic continuation and functional equation for it, by making fuller use of analysis in the spaces of valuation vectors and idèles themselves than Matchett had done. This thesis is the result of my work on his suggestion.

So it seemed that Matchett’s contributions were an important part of the story; providing the foundations for Tate’s full realization of Artin’s idèle-ized dream. (Sorry…)

The next few links were some LinkedIn profiles (probably not useful for someone who was PhD age in 1946…) but then I found a link to Chapter IV of a book by Della Dumbaugh and Joachim Schwermer entitled Emil Artin and Beyond - Class Field Theory and $L$-functions. This chapter, entitled “Margaret Matchett: Artin’s student at Indiana and her thesis,” contained both historical and mathematical background to her life. Indeed, the epigraph of the chapter contained part of Tate’s earlier quote above, while containing the full text of Margaret Matchett’s thesis. I feel a bit uncomfortable putting a PDF on this blog, but it’s not so hard to find and contains some fascinating background information, summarized here.

Born Margaret Stump on April 21st, 1918, Matchett originally wanted to be a librarian before catching the math bug during her undergrad at Butler University in Indiana. She arrived at Indiana University in September 1938, and quickly began taking classes and seminars with Artin, who had arrived at IU at roughly the same time. However, she met Gerald “Jerry” Matchett, who was a recently arrived PhD at Clark University in Massachusetts, and after marrying in 1942, gave up her academic career to follow him to his job at the War Relations board in Colorado, picking up an instructor position at the Army Specialized Training Program nearby. As her son Andrew (more on him later) put it, Margaret “certainly wanted to get married and to this particular young man. However, I know she felt a sense of loss that she would have to give up her graduate studies.”

So was the case that when her husband was drafted in March of 1944, she “instantly zipped” back to IU to continue her graduate work. Her break had been too long, so Artin gave her a new thesis problem, the one which she would eventually make into her dissertation. Her finished thesis remained unpublished (which, according to her son, annoyed Artin), and she would never publish in number theory again. After her husband was discharged in 1946, Margaret moved with him to Chicago, where they would spend the rest of their lives. They both got positions at the Illinois Institute of Technology, he as a tenure-track professor, and she as an instructor. Margaret would work through mathematics books on occasion, but she mainly focused on raising her kids and on her job as an instructor at Illinois Tech, and later at the University of Chicago Lab School, where she would eventually become head of the math department. There, besides being involved with gifted math education and developing new textbooks, she was involved with the School Mathematics Study Group and had a hand in creating the infamous “New Math.” After retiring in 1987, she lived a quiet life in Hyde Park before passing away in 2002. She was well known as a “a great inspiration to her students and her colleagues.”

Incidentally, a footnote here reveals that there was at least one of her students who was dissatisfied with her teaching. He groused that he had “very mixed feelings about her. Like most of the Lab school faculty I was close to, she was a communist. I was very alienated from my family, so they had a great influence on me, which I have come to regret.” As Dumbaugh and Schwermer remark, “he later viewed his political involvement as ‘a stupid waste of time.’ He still questions why the Lab School faculty ‘pushed him like that, and I am sure Ms. Matchett had a lot to do with it.’” Grumpy old man aside, it is indeed true that Margaret and Jerry were quite left-leaning. After Herbert Fuchs testified that both of them were members of the American Communist Party before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, both of them were hauled before the committee in 1955 to testify to their patriotism. The transcript of their testimony is equally fascinating and morbidly funny.

Mr. Tavenner. Were you acquainted with Phil Reno?

Mrs. Matchett. I claim the privilege of the fifth amendment.

Mr. Tavenner. Were you acquainted with Edward Scheunemann?

Mrs. Matchett. I claim the privilege of the fifth amendment.

Mr. Tavenner. Were you acquainted with Herbert Fuchs?

Mrs. Matchett. I claim the privilege of the fifth amendment.

Mr. Tavenner. Did you belong to a Communist Party cell or unit in Denver—

Mrs. Matchett. I claim the privilege.

Mr. Tavenner. Just a moment—to which each of those individuals belonged?

Mrs. Matchett. I claim the privilege of the fifth amendment.

Mr. Scherer. Herbert Fuchs said under oath that you were a member of the Communist Party. That was yesterday. Was he telling the committee the truth when he said that you were a member of the Communist Party?

Mrs. Matchett. I claim the privilege of the fifth amendment.

Mr. Scherer. You don’t deny, then, that his testimony is true?

Mrs. Matchett. I claim the privilege.

Mr. Tavenner. Are you now a member of the Communist Party? (Witness consulted her counsel) Mrs. Matchett. No.

Neither Margaret nor Jerry were ever formally charged or convicted.

At this point, I was very thoroughly engaged in this story of a woman I’d never met. So much so that I almost missed a footnote (“Editorial Notice”) that the authors had put:

The original copy of Margaret Matchett’s thesis, On the zeta function for ideles, is housed in the Indiana University Archives in Beddington, Indiana. Andrew Matchett, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Wisconsin Lacrosse and Margaret Matchett’s son, gave permission to publish this thesis for the very first time. The authors of this volume are extremely grateful to Andrew Matchett for granting this permission. Without it, the current treatise would have a large gap in its content.

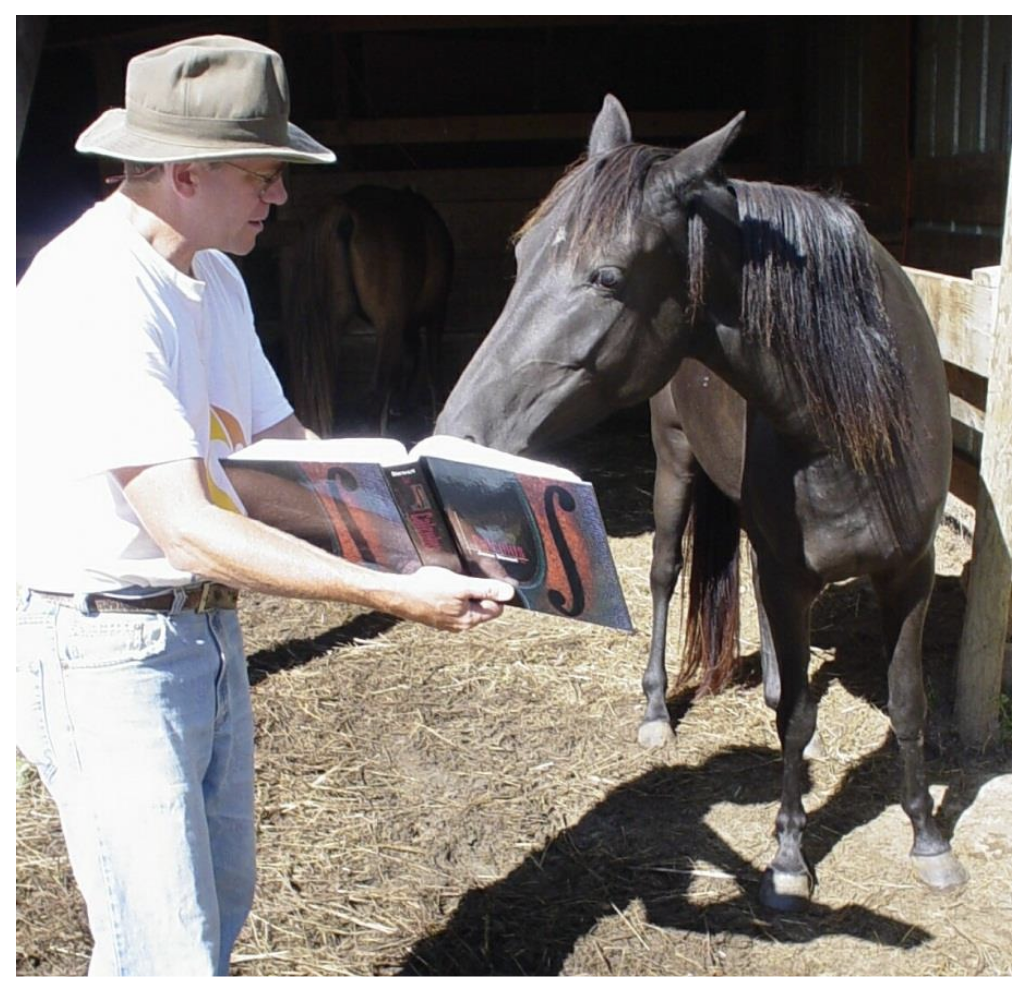

So it appeared that her son had entered the family business. Googling turned up an interview with Andrew Matchett, an installment of “Know Your Wisconsin Mathematician,” dated circa 2014. It’s a good interview, complete with a very educated horse:

I did find one line in particular amusing:

What was the influence of your family on your education?

My mother was a mathematician. She earned a Ph.D. under Emil Artin in algebraic number theory at Indiana University in 1946. Growing up, I knew that I did not want to be a mathematician, because I assumed that math was for girls.

(It’s interesting/funny how gender roles depend on context.) Then, I found a line that made me sit up straight.

Do you have any other comments? I have a son and daughter-in-law who are mathematicians. They are Philip Matchett Wood and Melanie Matchett Wood. They are both on the faculty in the Mathematics Department at University of Wisconsin (Madison).

Immediately, I knew where I had heard the name Matchett from, all the way at the start of this journey. It was from Melanie Matchett Wood’s name! Her step-grandma helped prove Tate’s thesis! What an insane connection?! Indeed, both Tate and Matchett have direct mathematical descendants here at UGA: Tate advised Carl Pomerance (also a former UGA professor!), who advised Paul Pollack, and Melanie’s first student was Jiuya Wang. Given that Tate did his thesis after Artin moved to Princeton and what we know of Margaret Matchett’s life, my guess is it’s unlikely the two ever met. Yet this still felt like a small wonder to discover; both of these mathematicians living so long ago, one far more famous than the other, creating a whole new way of thinking about number theory and continue to share a connection through the people they inspired decades later! No matter how common the refrain is, I think there’s something beautiful in that.

(Though, my Rutgers pride would not let me end without me mentioning that Philip Matchett Wood is a Scarlet Knight (PhD, 2009). RU Rah Rah!)